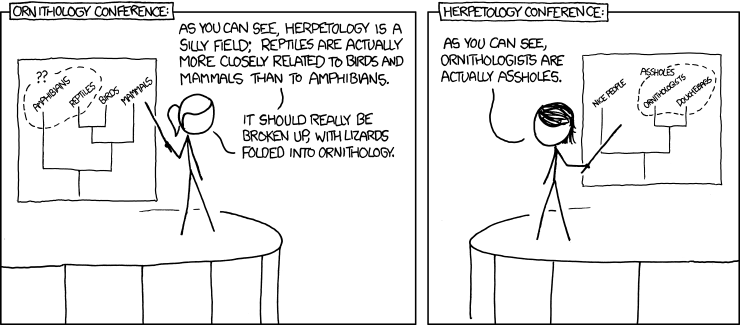

The reason? Imagine you have a kid, and your neighbor has 2 kids, then you both find out that really, one of their kids is sort of... yours. (-- awkward pause --) That's basically the problem here:

Herpetology is the study of reptiles and amphibians, however unraveling the evolutionary history of these two groups (along with birds) has shown us that birds are actually nested in among reptiles.

Now, to be fair, I think the comic has it wrong: I mean, shouldn't this justify lumping ornithology in a sub-discipline of herpetology?

Showing posts with label birds. Show all posts

Showing posts with label birds. Show all posts

Happy Turkey Day!

By

Paul

on

Thursday, November 25, 2010 at 9:46 AM

Labels: being human, birds, entertainment, evolution, fossils

Labels: being human, birds, entertainment, evolution, fossils

There's a Turkey in my fridge waiting to be cooked, but I couldn't resist writing a quick post full of links on today's official bird. Enjoy!

On this blog

External Links

- From Dinosaur to Turkey | NatGeo (Jump to Video, Facts)

- Your Holiday Dinosaur | Berkeley's UC Museum of Paleontology

- Turkey Day Science: What Do Gobblers Gobble? | USGS Western Ecological Research Center Blog

- This Thanksgiving, Make a Wish on a Dinosaur | Smithosonian Blog

Hungover Owls

It's been a while since there's been anything new posted on the hilariously vulgar blog "Fuck You, Penguin", so it totally made my day when a friend set me a link to "Hungover Owls" on tumblr.

It's absolutely hilarious - go check it out!

It's absolutely hilarious - go check it out!

Eastern Screech Owl: “Look, I’m sorry for blowing up earlier. It’s just…I can feel tequila…in my face.”

Wild Voices: Six Birds Species & Their Vocalizations

Nicely done video showcasing six species, narrated by scientists from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. In order of appearance: Common Loon, Barred Owl, Common Nighthawk, White-rumped Sandpiper (very cool vocalizations), Northern Cardinal, and Magnificent Frigatebird.

Like it? Let Cornell University know by clicking the video over to their YouTube page, and clicking on the "Like" button! IMO, videos like this beat the pants off of some of the other videos on their channel.

Like it? Let Cornell University know by clicking the video over to their YouTube page, and clicking on the "Like" button! IMO, videos like this beat the pants off of some of the other videos on their channel.

Which Came First: The Chicken or the Egg?

By

Paul

on

Friday, July 16, 2010 at 12:52 AM

Labels: birds, evolution, origins, reptiles, science literacy

Labels: birds, evolution, origins, reptiles, science literacy

I was surprised to hear my local news anchor announce that scientists have "finally" answered the question of which came first: the chicken or the egg. The story is making rounds in the news - for example here, here, here, and here - but they're getting it wrong.

Three words: Bad. Science. Journalism.

Now, before you think I'm going off the deep end here - I'm not the only one who thinks this is crappy science journalism, and I try to keep things in perspective...

Back to our question. Ignoring the original causality dilemma, didn't we clear this up a century or two ago? The egg came first (yes, even the shelled egg) and it arrived on the scene a couple hundred million years earlier, so it isn't even close!

Despite the horrible news coverage, the real story behind the bad headline is interesting. In short, molecular modeling work suggests the role of a certain protein (ovocleidin-17) is to catalyze the deposition of calcium during the formation of the egg shell in chickens. This has been it's suspected role for a few years now, but it's great to have another line of evidence that also suggests this protein's function, plus it gives us a better understanding of how eggs are produced.

The news story does has a silver lining. After covering it, my local Fox news anchors went on to mention that the authors of the research did point out that birds evolved from dinosaurs, and that perhaps we should rephrase the question in terms of dinosaurs versus dinosaur eggs. If you missed that, let me reiterate: my local Fox News anchors pointed out that birds evolved from dinosaurs!

Given the results of a recent poll, that's a welcome statement on the evening news.

These are similar to previous polling results from Gallup on Evolution, Creationism and Intelligent Design.

Three words: Bad. Science. Journalism.

Now, before you think I'm going off the deep end here - I'm not the only one who thinks this is crappy science journalism, and I try to keep things in perspective...

Back to our question. Ignoring the original causality dilemma, didn't we clear this up a century or two ago? The egg came first (yes, even the shelled egg) and it arrived on the scene a couple hundred million years earlier, so it isn't even close!

Despite the horrible news coverage, the real story behind the bad headline is interesting. In short, molecular modeling work suggests the role of a certain protein (ovocleidin-17) is to catalyze the deposition of calcium during the formation of the egg shell in chickens. This has been it's suspected role for a few years now, but it's great to have another line of evidence that also suggests this protein's function, plus it gives us a better understanding of how eggs are produced.

The news story does has a silver lining. After covering it, my local Fox news anchors went on to mention that the authors of the research did point out that birds evolved from dinosaurs, and that perhaps we should rephrase the question in terms of dinosaurs versus dinosaur eggs. If you missed that, let me reiterate: my local Fox News anchors pointed out that birds evolved from dinosaurs!

Given the results of a recent poll, that's a welcome statement on the evening news.

In the United States, almost half of respondents (47%) believe that God created human beings in their present form within the last 10,000 years, while one-third (35%) think human beings evolved from less advanced life forms over millions of years.

Half of people in the Midwest (49%) and the South (51%) agree with creationism, while those in the Northeast are more likely to side with evolution (43%).

Related Links:

- Bad science journalism the fault of chickens or eggs? | Thoughtomics by Lucas Brouwers

- Freeman C. L., Harding J. H., Quigley D., Rodger P. M. 2010. Structural Control of Crystal Nuclei by an Eggshell Protein. Angewandte Chemie International Ed. 49(30) doi: 10.1002/anie.201000679

Do ornithologists agree birds evolved from dinosaurs?

If you like birds, dinosaurs, anatomy, evolution or paleontology, you need to go read this post... twice. Here's why...

Over at Tetrapod Zoology, Darren Naish has a great exposition on the question above (as well as a recommendation/review of a book that any bird-nerd should have on their shelf) which I encourage you to go read at least once. The title of Darren's post (and his book recommendation) is Gary Kaiser's The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution.

I find that most people who aren't biologists or bird-nerds are unaware of the idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs. While most of my ornithologist friends accept the idea, I'm not sure how many really understand the evidence behind the claim (in their defense - it's well outside of their areas of expertise, so this is hardly a criticism). That said, this book (and even Darren's post) could help clear up some of that evidence.

Here's a little of what Darren writes on the origin of birds...

Over at Tetrapod Zoology, Darren Naish has a great exposition on the question above (as well as a recommendation/review of a book that any bird-nerd should have on their shelf) which I encourage you to go read at least once. The title of Darren's post (and his book recommendation) is Gary Kaiser's The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution.

I find that most people who aren't biologists or bird-nerds are unaware of the idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs. While most of my ornithologist friends accept the idea, I'm not sure how many really understand the evidence behind the claim (in their defense - it's well outside of their areas of expertise, so this is hardly a criticism). That said, this book (and even Darren's post) could help clear up some of that evidence.

Here's a little of what Darren writes on the origin of birds...

Kaiser is convinced by the evidence for the dinosaurian origin of birds, and long sections of the book are devoted to discussing the similarities and differences seen between birds and their non-avian relatives*. The notion that birds cannot be dinosaurs is heavily promoted in the ornithological literature - most notably in Alan Feduccia's The Origin and Evolution of Birds (Feduccia 1996). Because Feduccia's book is one of the most visible of volumes on bird evolution, audiences can be forgiven for thinking that ornithologists as a whole reject the hypothesis of a dinosaurian ancestry for birds. This is absolutely not true, and those interested should take every opportunity to note that all of Feduccia (et al.'s) criticisms are invalid or erroneous (e.g., that non-avian theropods are too big to be ancestral to birds, that they occur too late in the fossil record, that their anatomy bars them from avian ancestry, and that other Mesozoic reptiles make better potential bird ancestors). It is also worth noting that many of Feduccia's proposals about the phylogeny of neornithines are idiosyncratic and that his volume does not accurately represent current thinking on avian evolutionary history. The Inner Bird helps provide part of the antidote, bringing home the point that the dinosaurian origin of birds is well supported and robust, and adopted by many ornithologists interested in palaeontology.You can read the rest of the article here.

Mid-week Reptilian #21: House Sparrow

I'm writing this post in an airport as I wait for my very delayed flight (it's cool - I got a big juicy travel voucher and a couple meal vouchers, so Delta and I are still best buds). I had planned to get some work done, but as I sit here this week's reptilians are zipping around the terminal feasting on crumbs (practically begging me to write a blog post about them), trying to procreate, and all the while unknowingly flaunting their ability to coexist along side humans. It's that ability that has made the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) one of the most successful bird species on the planet.

Figure 1: Male House Sparrow visiting a backyard in Toronto, Canada.

Mid-week Reptilian #19: Indian Peafowl (aka Peacock)

Better known in the U.S. as the peacock, the Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) is a common domestic bird, native to India. They're in the order Galliformes with chickens, quail, turkeys, grouse and pheasants, and are in the same family as the pheasants, partridges and turkeys: Phasianidae.

Male peafowl are known as peacocks, and the females are accordingly called peahens. If you know some Spanish, or recall reading this post around Thanksgiving last November, you'll recognize the genus name Pavo is also the spanish word for the turkey (Meleagris gallipavo). Upon seeing turkeys brought back from the Americas to Europe, the birds' resemblance to the peafowl earned them the shared name.

Many believe that peacocks fan their tails, but those long gaudy feathers are not tail feathers! Instead, they're modified feathers called upper tail coverts, which grow from just above the tail and cover the base of the actual tail feathers.

Don't believe me? Just search for images of "peacock butt" on the web, and you'll see that the actual (shorter) tail feathers are right where you'd expect them to be, on the back of the fan of upper tail coverts. For example...

Still, that train of iridescent feathers is quite a stunning site. If you haven't recently seen one up close, here's a high resolution photo of a male photographed in 2009 at the Denver Zoo. Click to enlarge...

Male peafowl are known as peacocks, and the females are accordingly called peahens. If you know some Spanish, or recall reading this post around Thanksgiving last November, you'll recognize the genus name Pavo is also the spanish word for the turkey (Meleagris gallipavo). Upon seeing turkeys brought back from the Americas to Europe, the birds' resemblance to the peafowl earned them the shared name.

Many believe that peacocks fan their tails, but those long gaudy feathers are not tail feathers! Instead, they're modified feathers called upper tail coverts, which grow from just above the tail and cover the base of the actual tail feathers.

Don't believe me? Just search for images of "peacock butt" on the web, and you'll see that the actual (shorter) tail feathers are right where you'd expect them to be, on the back of the fan of upper tail coverts. For example...

Figure 1: Hind view of a displaying peacock

showing the tail feathers & bases of the modified

upper tail coverts that form the fan. The tips

of the folded wings are also visible. [Source]

of the folded wings are also visible. [Source]

Still, that train of iridescent feathers is quite a stunning site. If you haven't recently seen one up close, here's a high resolution photo of a male photographed in 2009 at the Denver Zoo. Click to enlarge...

Figure 2: The full frontal assault of the peacock. Click to zoom in.

Raptors and Wind Farms

By

Paul

on

Saturday, May 8, 2010 at 8:03 PM

Labels: birds, conservation, humans vs nature, technology

Labels: birds, conservation, humans vs nature, technology

Note: I've been going through a backlog of draft posts and pulling out anything still worth posting. This one, sharing video on the hazards posed by wind farms to resident and migrating raptors, was accidentally saved as a draft back in October 2009.

I recently saw this video when it was posted by a friend on facebook. He summed it up nicely:

Here's a more complete version of the story:

Unfortunately, wind farms often go up in prime airspace for locally breeders and migrating birds of prey, and can cause significant mortality from collisions like these.

I recently saw this video when it was posted by a friend on facebook. He summed it up nicely:

[This is why] the placement of wind turbines needs to be very carefully considered.

Here's a more complete version of the story:

Unfortunately, wind farms often go up in prime airspace for locally breeders and migrating birds of prey, and can cause significant mortality from collisions like these.

The Cost of the Gulf Coast Oil Spill

By

Paul

on

Friday, April 30, 2010 at 1:30 PM

Labels: birds, conservation, environment, humans vs nature, mammals, natural resources, nature, reptiles, technology

Labels: birds, conservation, environment, humans vs nature, mammals, natural resources, nature, reptiles, technology

This post will be updated regularly. There are links below to related articles, blog posts, and other resources on the flora and fauna affected by the gulf coast BP oil spill. If you know of other links or suggestions, please send them to me via email or in the comments below.

Bloggers, biologists, naturalists, science writers... I need your help. Life is about to get very bad for the inhabitants of the Gulf Coast, with the first waves of raw crude oil projected to reach shore in the coming days, if it hasn't already. While this will certainly have an impact on local economies and an even bigger impact on those who make their living from those waters, there will be a great many other living organisms and even entire ecosystems that will be utterly devastated by the spill.

So why don't more people seem to care? While there is no single answer to that question , it is in part because pretty much every single person has absolutely no idea that most of the affected species even exist. It's hard to fault someone for not caring about something they don't even know exists, and I'd bet most people would care if they only knew... That, my friends, is where I need your help!

Bloggers, biologists, naturalists, science writers... I need your help. Life is about to get very bad for the inhabitants of the Gulf Coast, with the first waves of raw crude oil projected to reach shore in the coming days, if it hasn't already. While this will certainly have an impact on local economies and an even bigger impact on those who make their living from those waters, there will be a great many other living organisms and even entire ecosystems that will be utterly devastated by the spill.

So why don't more people seem to care? While there is no single answer to that question , it is in part because pretty much every single person has absolutely no idea that most of the affected species even exist. It's hard to fault someone for not caring about something they don't even know exists, and I'd bet most people would care if they only knew... That, my friends, is where I need your help!

How you can help...

To help raise awareness of the environmental costs of the gulf coast oil spill, I'm asking others to take at least one of the follow actions to draw attention to particular species and ecosystems affected by the spill:- Share this post, and this request with others, and be creative about it -- encourage your local news paper's science writer to showcase the environmental costs of the spill, organize a public talk by local conservation groups, university or government researchers, and so on. Check back now and then and share some of the posts below with your family, friends and coworkers.

- If you have a blog, choose an organism -- plant, animal, or other -- and tell the rest of us about it. No blog? No problem... you can always write a guest-post for someone else's blog, or use other media outlets. You can make a video and post it on youtube, send some info you your local newscasters, do whatever you can think of! Share pictures, natural history facts, economic value, whatever you can come up with to convey to the public why anyone should give a rat's tail about the demise of your chosen subject. Once you've done that, if it's on the web, please send me the link and I'll include it below.

- Stash some cash if you can, and consider donating to the recovery efforts. I'll post more information below once I get the time to offer up suggestion.

Related Links...

Birds- Bad Place, Bad Timing for and Oil Spill | Round Robin (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Gulf Coast Birds in Danger | Frank Gill, PhD. (CNN Opinion piece)

- West Indian Manatee | The Obligate Scientist

- Impacts on Wildlife of the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill | Ninjameys (Natural History Blog)

- Watching and Waiting | Living Alongside Wildlife

- Oil Spill Wildlife Rescue: Why Some Animals Receive Priority Care | Discovery News

- Pictures: Gulf Oil Spill Hits Land -- And Wildlife | National Geographic

- Photos related to the 2010 gulf coast oil spill | www.Flickr.com

- Info on Methane Hydrates | The Obligate Scientist

- Gulf Oil Slick | Blog with great areal footage, environmental news

- NOAA's website on the Deep Water Horizon Spill, Gulf of Mexico | NOAA.gov

- USFWS wesbite on the oil spill response | FWS.gov

- EPA's website on the spill | EPA.gov

- Tracking the oil spill | CNN

- Cool Green Science | Nature Conservancy's Blogs

- Gulf Coast Wildlife Workers Prepare For Worst | NPR's All Things Considered

Mid-week Reptilian #15: American Robin

By

Paul

on

Tuesday, March 30, 2010 at 7:45 PM

Labels: birds, mid-week reptilians, natural variation, nature, wildlife

Labels: birds, mid-week reptilians, natural variation, nature, wildlife

The American Robin (Turdus migratorius) is a common bird in North America, and like the Canada Goose, is one of those birds that most anyone can recognize. This week, I thought I'd share a particularly odd looking individual I recently photographed along with the usual taxonomical tidbits about this species.

So here's the rundown on these little feathered archosaurs. American Robins a kind of thrush, making them members of that very diverse order, Passeriformes - the "perching birds" - and kin to the other "song birds" (aka the oscines) comprising the suborder Passeri. Like other oscines, American Robins have a well developed syrinx, and the ability to learn complex vocalizations. (More on the oscine syrinx and can be found here in The Physics of Birdsong by Mindlin & Laje, and in this article on the musculature of the syrinx. If you'd like to hear some Robin vocalizations then hop on over to Cornell's Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds and browse some of their recordings of this species.)

Robins are common enough that every now and then you spot an odd one. Below are some photographs of an aberrant individual I recently photographed in Columbus, OH. This individual was sporting a set of feathers that -- for one reason or another -- are missing some color.

Now, before you get carried away and chalk this individual's condition up to yet another point mutation, consider what else might have caused this lack of pigment. While most people get the idea of genetically based coloration, they generally think in terms of simple mutations that shut down (either completely or partially) the production of a pigment. You can read more on bird pigmentation here.

It just so happens that producing colored tissues (or hair, or feathers, or scales, or whatever) is a bit more complicated than just producing some pigment, requiring the functionality of various chemical pathways and cellular structures (e.g. organelles like melanosomes) to make sure the right amount of the right color ends up in the right place.

In birds and other organisms (like humans, for example) there can be changes later in life that in one way or another cause the loss of pigmentation -- for example an autoimmune disorder that wipes out melanocytes, or some sort of metabolic problem that interferes with an individuals (otherwise normal) capacity to produce pigment.

I could probably write a series of posts on pattern formation and coloration, but alas that probably won't happen any time soon (...day job). In any case, I've blabbed enough. I'll leave you to ponder this silvery American Robin and it's not-so-silver lunch buddy. As always, click the pics to enlarge.

Figure 1: Robins are sexually dimorphic, and males can often be

IDed by their darker heads. I photographed this (agitated) male

and the odd bird below in Columbus, Ohio on 26 March 2010.

So here's the rundown on these little feathered archosaurs. American Robins a kind of thrush, making them members of that very diverse order, Passeriformes - the "perching birds" - and kin to the other "song birds" (aka the oscines) comprising the suborder Passeri. Like other oscines, American Robins have a well developed syrinx, and the ability to learn complex vocalizations. (More on the oscine syrinx and can be found here in The Physics of Birdsong by Mindlin & Laje, and in this article on the musculature of the syrinx. If you'd like to hear some Robin vocalizations then hop on over to Cornell's Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds and browse some of their recordings of this species.)

Robins are common enough that every now and then you spot an odd one. Below are some photographs of an aberrant individual I recently photographed in Columbus, OH. This individual was sporting a set of feathers that -- for one reason or another -- are missing some color.

Figure 2: A very pale (some would say, hypomelanistic) individual

foraging along side the same (normal) male in the photograph above.

Now, before you get carried away and chalk this individual's condition up to yet another point mutation, consider what else might have caused this lack of pigment. While most people get the idea of genetically based coloration, they generally think in terms of simple mutations that shut down (either completely or partially) the production of a pigment. You can read more on bird pigmentation here.

It just so happens that producing colored tissues (or hair, or feathers, or scales, or whatever) is a bit more complicated than just producing some pigment, requiring the functionality of various chemical pathways and cellular structures (e.g. organelles like melanosomes) to make sure the right amount of the right color ends up in the right place.

In birds and other organisms (like humans, for example) there can be changes later in life that in one way or another cause the loss of pigmentation -- for example an autoimmune disorder that wipes out melanocytes, or some sort of metabolic problem that interferes with an individuals (otherwise normal) capacity to produce pigment.

I could probably write a series of posts on pattern formation and coloration, but alas that probably won't happen any time soon (...day job). In any case, I've blabbed enough. I'll leave you to ponder this silvery American Robin and it's not-so-silver lunch buddy. As always, click the pics to enlarge.

Figure 3: Same individuals. Here the pale bird was observed pushing

away the normal bird while both foraged for worms. It seems plausible

that the pale bird is female. The two seemed to stay near one another

(for the most part) during the 15-20 minutes I observed them.

Figure 4: A closer look at the pigmentation and wear of the wing and

tail feathers. Such wear may indicate more substantial problems in

feather structure than just pigmentation. Notice the tertials (top-most

wing feathers visible below the back feathers) are asymmetric: the right

being more darkly colored than the left. In flight this bird looked very pale.

tail feathers. Such wear may indicate more substantial problems in

feather structure than just pigmentation. Notice the tertials (top-most

wing feathers visible below the back feathers) are asymmetric: the right

being more darkly colored than the left. In flight this bird looked very pale.

Mid-week Reptilian #12: Struthio camelus

By

Paul

on

Wednesday, March 3, 2010 at 10:36 AM

Labels: birds, evolution, mid-week reptilians, reptiles

Labels: birds, evolution, mid-week reptilians, reptiles

As the heaviest and tallest living bird, the Ostrich (Struthio camelus) is probably the most familiar of all flightless birds second only to penguins. While flightlessness has evolved numerous times in a variety of different bird groups, it's the norm among Ostriches and their closest relatives - the ratites.

As the heaviest and tallest living bird, the Ostrich (Struthio camelus) is probably the most familiar of all flightless birds second only to penguins. While flightlessness has evolved numerous times in a variety of different bird groups, it's the norm among Ostriches and their closest relatives - the ratites.Most people are familiar with these big, showy, eye catching animals. They are common in zoos, frequently seen images in popular media, and recently have even gained popularity as livestock (drumstick, anyone?). Ostriches commonly appear in documentaries, such as this recent appearance (as cat food) in the latest BBC series, Life (see below).

(Americans apparently can't handle Attenborough, so unfortunately we get Oprah instead. )

As you may have already noticed, Ostriches aren't just some stretched out version of your typical bird. So what makes them so distinct? To fully appreciate what makes these towering descendants of dinosaurs so darn interesting, it helps to look into their evolutionary history -- one that is shared with their closest living relatives, the other ratites.

Ratites are a group of flightless birds (order Struthioniformes, though some elevate the families below to order status) spread out over South America, Africa and Australasia. They're a great example of allopatric speciation, with the different species having diverged from one another as the continents spread apart during the past hundred million years or so.

Figure 1: Pangea breaking up starting at ~225 million years ago.

As a group, the taxonomic relationships within the ratites falls cleanly over their geographic distributions. Excluding extinct species like the freakishly huge Moas, and other groups that have recently been associated with the ratites (i.e., the Tinamous), their distributions are as follows:

Australasian Ratites

1. Family Cassuariidae

- Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

- Cassowary (3 species; Southern Casuarius casuarius, Dwarf C. bennetti, Northern C. unappendiculatus.)

2. Family Apterygidae

- Kiwis (5+ species, all in the genus Apteryx)

African Ratites

3. Familiy Struthionidae

- Ostrich (Struthio camelus)

South American Ratites

4. Family Rheidae

- Rheas (2 species; Greater Rhea americana, and Lesser R. pennata)

If that's news to you, lets just say it out loud one more time: Ostriches have claws!!

Figure 2: Details of the wingtip of the Ostrich, drawn circa 1898.

[Source: The structure and classification of birds (full text).]

Fortunately for zoo visitors and Ostrich farmers, they didn't retain TOO many of their ancestors' other dinosaurian features. Imagine getting a bite from one of these!

Figure 3: The ostrich farmer's worst

What Caused All These Dead Birds in Tennessee?

Was it an outbreak of infectious disease? Did someone decide these birds were "agricultural pests" and deliberately poison them? Maybe they all were accidentally exposed to something toxic, or flew into traffic or power lines? Lots of folks down in Clarksville, Tennessee would love to know what actually killed a few hundred birds along a nearby road earlier this week...

Now, the birds shown are Red-winged Blackbirds and Common Grackles -- common species to find along side non-native European Starlings in big flocks of "blackbirds". From the condition and seemingly localized occurrence of the bird carcasses shown in the video, I'm pretty comfortable ruling out traffic or power-line collisions as the source of all these dead birds. I'd be much more included to put my money on poisoning... and probably deliberate poisoning.

Why? Well, this sort of thing actually isn't all that unheard of... Take, for example, a case from New Jersey which previously made the news when birds started actually falling from the sky.

Oh, and if you wondered what was meant by "a permit" in the first video above, I should mention that the New Jersey incident (and this one from PA) were both part of control efforts. While hardly a pleasant sight, these large flocks of (mostly?) European Starlings were poisoned after consideration and approval by the USDA.

Getting back to the original question of "what happened?" we (fortunately) won't need to rely solely on speculation in this case! That said, we do still have to wait a bit and see what information comes back with those lab results...

(To be continued!)

Now, the birds shown are Red-winged Blackbirds and Common Grackles -- common species to find along side non-native European Starlings in big flocks of "blackbirds". From the condition and seemingly localized occurrence of the bird carcasses shown in the video, I'm pretty comfortable ruling out traffic or power-line collisions as the source of all these dead birds. I'd be much more included to put my money on poisoning... and probably deliberate poisoning.

Why? Well, this sort of thing actually isn't all that unheard of... Take, for example, a case from New Jersey which previously made the news when birds started actually falling from the sky.

[Source: WKRG.com News]

Oh, and if you wondered what was meant by "a permit" in the first video above, I should mention that the New Jersey incident (and this one from PA) were both part of control efforts. While hardly a pleasant sight, these large flocks of (mostly?) European Starlings were poisoned after consideration and approval by the USDA.

Getting back to the original question of "what happened?" we (fortunately) won't need to rely solely on speculation in this case! That said, we do still have to wait a bit and see what information comes back with those lab results...

(To be continued!)

2010 Great Backyard Bird Count!!

Looking for an excuse to get outside this weekend? Consider participating in the Great Backyard Bird Count! Go solo, take the family, maybe a friend or two, or maybe even join your local Audubon Society chapter or birding club and head outside to do some bird watching!

Aside from being a fun activity (and a great opportunity to learn more about your local birds), the data you collect are compiled along with data from thousands of others all across the country and made publicly available. As of late Friday night, here's how many checklists have been submitted so far:

To give you an idea of what can be done with the data, here's an animated map of past observations of Common Redpolls in North America. This small northern finches tend to come down south for the winter -- but only every other year or so. This pattern can be seen in the data, as illustrated in this animated map...

More maps and data can be found on the Results section of the Great Backyard Bird Count website.

Aside from being a fun activity (and a great opportunity to learn more about your local birds), the data you collect are compiled along with data from thousands of others all across the country and made publicly available. As of late Friday night, here's how many checklists have been submitted so far:

To give you an idea of what can be done with the data, here's an animated map of past observations of Common Redpolls in North America. This small northern finches tend to come down south for the winter -- but only every other year or so. This pattern can be seen in the data, as illustrated in this animated map...

More maps and data can be found on the Results section of the Great Backyard Bird Count website.

Feather Color Revealed in Dinosaurs

Unrelated to my previous post, news came today from the journal Nature that a group of scientists have used SEM techniques to reveal color patterns from some well preserved dinosaur feathers -- cool stuff!

Here's a figure from the paper, showing some of the melanosomes (pigment containing structures within cells).

In addition to the coloration details, this paper also gets into other aspects of feather structure confirming that these structures are indeed feathers:

For further discussion of the paper, see...

Here's a figure from the paper, showing some of the melanosomes (pigment containing structures within cells).

"Melanosomes in the integumentary filaments of

the dinosaur Sinornithosaurus (IVPP V12811).

a, Optical photographs of part of the holotype and SEM samples (insets).

b, Mouldic phaeomelanosomes.

c, Aligned eumelanosomes preserved as solid bodies (at arrows).

c, Aligned eumelanosomes preserved as solid bodies (at arrows).

d, Strongly aligned mouldic eumelanosomes.

Scale bars: a, main panel, 50mmand inset, 5 mm; b–d, 2 mm."

[Source: Nature article, via The Z-Letter Archive]

In addition to the coloration details, this paper also gets into other aspects of feather structure confirming that these structures are indeed feathers:

Our results demonstrate conclusively that the integumentary filaments of non-avian theropod dinosaurs are epidermal structures. In birds, melanin is synthesized endogenously in specialized pigment producing cells, melanocytes, that occur primarily in the dermis; the melanocytes migrate into the dermal pulp of the developing feather germ, where the melanin is packaged into melanosomes and then those melanosomes are transferred to keratinocytes for deposition into developing feathers. In various avian species melanin granules also form, and are apparently retained, in dermal melanocytes; melanin granules can form a discrete layer in the dermis, but below, and not as part of, the collagen layer. The occurrence of melanosomes embedded inside the filaments of Jehol non-avian dinosaurs thus confirms that these structures are unequivocally epidermal structures, not the degraded remains of dermal collagen fibres, as has been argued recently. Our work confirms that these filaments are probably the evolutionary precursors of true feathers, and it will be interesting to determine whether any fossil filaments might relate to other kinds of epidermal outgrowths in modern birds.

For further discussion of the paper, see...

- Dinosaurs, now available in colour | Dave Hone's Archosaur Musings

- Dinosaurs in color | The Z-letter Archive

- Moving Dinosaurs Into Technicolor | The Loom

- Feathered dinosaurs -- in color! | Why Evolution Is True

New bird-like dinosaur fossil?

Update: Links to the articles in Science are here and here. Also see the posts here and here on Dave Hone's blog.

Looks like there might be something tomorrow (27 Jan 2010) in the journal Science announcing a new bird-like dinosaur fossil? Details over at Dave Hone's blog in the posts:

Looks like there might be something tomorrow (27 Jan 2010) in the journal Science announcing a new bird-like dinosaur fossil? Details over at Dave Hone's blog in the posts:

- The wonderfully weird alvarezsaurs by Dave Hone

- A brief history of Alvarezsaur research by Jonah Choiniere

A Dinosaur on the Christmas Dinner Table

By

Paul

on

Thursday, December 24, 2009 at 11:27 AM

Labels: amphibians, birds, dinosaurs, education, evolution, mammals, origins, primates, reptiles

Labels: amphibians, birds, dinosaurs, education, evolution, mammals, origins, primates, reptiles

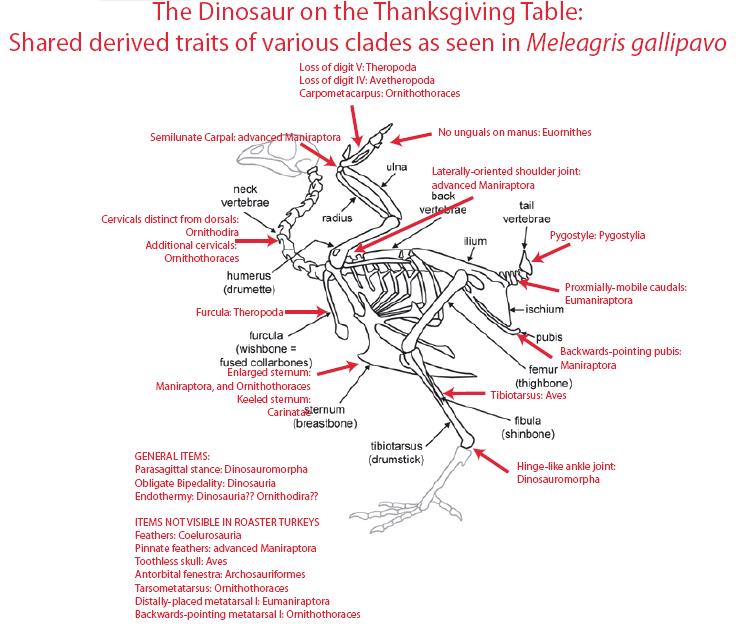

If you recall my post from back around Thanksgiving, the Wild Turkey -- like all birds -- is a modern day dinosaur. What better opportunity to share this little fact with your friends and family than over the Christmas Turkey?

If you recall my post from back around Thanksgiving, the Wild Turkey -- like all birds -- is a modern day dinosaur. What better opportunity to share this little fact with your friends and family than over the Christmas Turkey?Below are some resources for turning the remains of your holiday feast into a biology lesson, but before we get into details I want to first answer a simple question: What exactly is a dinosaur anyway?

Dinosaur's are a group of (mostly extinct) reptiles that arose around the early Triassic period about 230 million years ago (mya). They persisted until the mass extinction event that occurred 65mya at the end of the Cretaceous period, (also the end of the Mesozoic era and start of the Cenozoic era), when all of the dinosaur lineages save modern birds died out.

To put this talk of dinosaurs and birds into perspective, lets take a crash course in vertebrate taxonomy. Starting with the ancestor of all land vertebrates, we can follow evolution forward to the present, noting major points of divergence along the way. We're of course skipping a lot, taking the fast track from the first vertebrate land animals to modern day birds.

The first amphibian-like terrestrial tetrapods appeared over 350mya (Late Devonian into the Carboniferous period), with the Synapsids (whose descendants became the modern mammals) splitting off 25+ million years later. Another 25 million years or so later, ancestral turtles and other Testudines appeared, then the sphenodonts (the tuatara) and the squamates (lizards and snakes), then crocodilians, then dinosaurs and birds.

These relationships can be summarized as follows (here I've included proper group names as well as extant representatives):

- Amniotes - Descendants of the first egg-laying terrestrial vertebrates (~ 340mya) split around ~325mya

- Synapsids - Mammalian ancestors

- ...

- Mammals ~ 200 mya

- Primates ~ 55+ mya

- Human-Chimp Split ~ 5-10 mya

- Saurapsids - Modern Reptilians

- Anapsids - Turtles

- Diapsids - Other modern reptiles (including birds), split ~ 300mya

- Lepidosauria -Tuatara, Lizards and Snakes

- Sphenodonts - Tuatara

- Squamates - Lizards, Snakes

- Archosauria - Crocodilians, Dinosaurs (including birds)

- Dinosauria - Two dinosaur groups diverged ~250 mya

- Ornithischia - "bird-hipped", beaked - but not birds!

- Saurischia - "lizard-hipped", toothed ancestors of birds.

- Sauropodomorpha - big herbivores like Diplodicus.

- Theropoda - bipedal carnivores like T. rex, Velociraptor and...

- Aves - modern birds, originating ~ 150mya

So how do you bring all this information to the dinner table? Well the easiest way to see the relationship between dinosaurs and birds is from the differences and similarities in their skeletal structure.

Other ideas can be found here, and for a nice reference you can bring with you to the Christmas dinner table...

Resources:

- Prothero, S. 2007. Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters. Columbia Univ. Press.

- The Dinosauria, from the University of California Museum of Paleontology website.

- Wikipedia (links above).

- Wedel, Matt. Your Holiday Dinosaur, University of California Museum of Paleontology website.

- Holtz, Tom. Your Thanksgiving/Christmas Therapod from Dave Hone's Archosaur Musings.

Mid-week Reptilian #8: Happy Turkey Day!

What more appropriate reptilian to showcase this holiday than the one on the dinner table? How about it's wild counterpart - the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo).

The Wild Turkey is the largest of the 2 extant turkey species (the other being the Oscillated Turkey of S. America). There are around six recognized subspecies (nominate South Mexico M. g. gallopavo, Gould's M. g. mexicana, Eastern M. g. silvestris, Florida M. g. osceola, Merriam's M. g. merriami, and Rio Grande M. g. intermedia) and a variety of domestic breeds including the somewhat pitiful breed most Americans will be carving up this Thanksgiving. Turkeys are classified in the order Galliformes, which includes the other chicken-, grouse- and pheasant-like birds. In the past turkeys belonged to their own family (Meleagrididae), but recently they've been deemed more closely related to the grouse and pheasants lumping the three previously distinct family groups into the family Phasianidae.

Turkey's received their common name from their early arrival to Europe, when they were imported to Turkey from the new world. They became know as "Turkey Fowl" on the market, and as Europeans moved to the Americas, the name stuck. In spanish many call turkey pavo, likely from early European confusion with Peafowl (genus pavo), and in parts of Central American and Mexico turkey are known commonly by their Nahuatl name of guajolote.

Turkey are conspicuous birds, and not surprisingly hold a place in U.S. history. Aside from the Thanksgiving tradition, there is also Benjamin Franklin's rather famed criticism of the Bald Eagle as our national emblem. In a 1784 letter to his daughter Sarah, he compares a few other birds with that "bird of bad moral character", the eagle - including the Wild Turkey.

The Wild Turkey is the largest of the 2 extant turkey species (the other being the Oscillated Turkey of S. America). There are around six recognized subspecies (nominate South Mexico M. g. gallopavo, Gould's M. g. mexicana, Eastern M. g. silvestris, Florida M. g. osceola, Merriam's M. g. merriami, and Rio Grande M. g. intermedia) and a variety of domestic breeds including the somewhat pitiful breed most Americans will be carving up this Thanksgiving. Turkeys are classified in the order Galliformes, which includes the other chicken-, grouse- and pheasant-like birds. In the past turkeys belonged to their own family (Meleagrididae), but recently they've been deemed more closely related to the grouse and pheasants lumping the three previously distinct family groups into the family Phasianidae.

Figure 1: Two male Eastern Wild Turkeys doing a courtship display.

Figure 2: The completely unrelated Turkey Vulture, here regally poised atop

a decaying deer carcass (for your post-Thanksgiving-dinner pleasure).

Turkey's received their common name from their early arrival to Europe, when they were imported to Turkey from the new world. They became know as "Turkey Fowl" on the market, and as Europeans moved to the Americas, the name stuck. In spanish many call turkey pavo, likely from early European confusion with Peafowl (genus pavo), and in parts of Central American and Mexico turkey are known commonly by their Nahuatl name of guajolote.

Turkey are conspicuous birds, and not surprisingly hold a place in U.S. history. Aside from the Thanksgiving tradition, there is also Benjamin Franklin's rather famed criticism of the Bald Eagle as our national emblem. In a 1784 letter to his daughter Sarah, he compares a few other birds with that "bird of bad moral character", the eagle - including the Wild Turkey.

For in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours; the first of the species seen in Europe, being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding table of Charles the Ninth. He is, besides, (though a little vain and silly, it is true, but not the worse emblem for that,) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards, who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.

Mid-week Reptilians #7: High Altitude Flamingos!

While I've been busy lately with thesis work (among other things), I recently found out some fellow grad students won the Audience's Choice award in the first of The Scientist Video Awards. Here's a brief article on some of that work on these magnificent birds.

Job well done folks!

Job well done folks!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)